Adhering to our animalistic theme, I’d like to introduce to you Kalila wa Dimna, an ancient Indian text containing a collection of fables. According to Professor Nasrin Rahimieh, Kalila wa Dimna was written by Brahman philosopher Bidpai for King Dabshalim, serving as a guide on how to “obtain the loyalty of his subjects”.

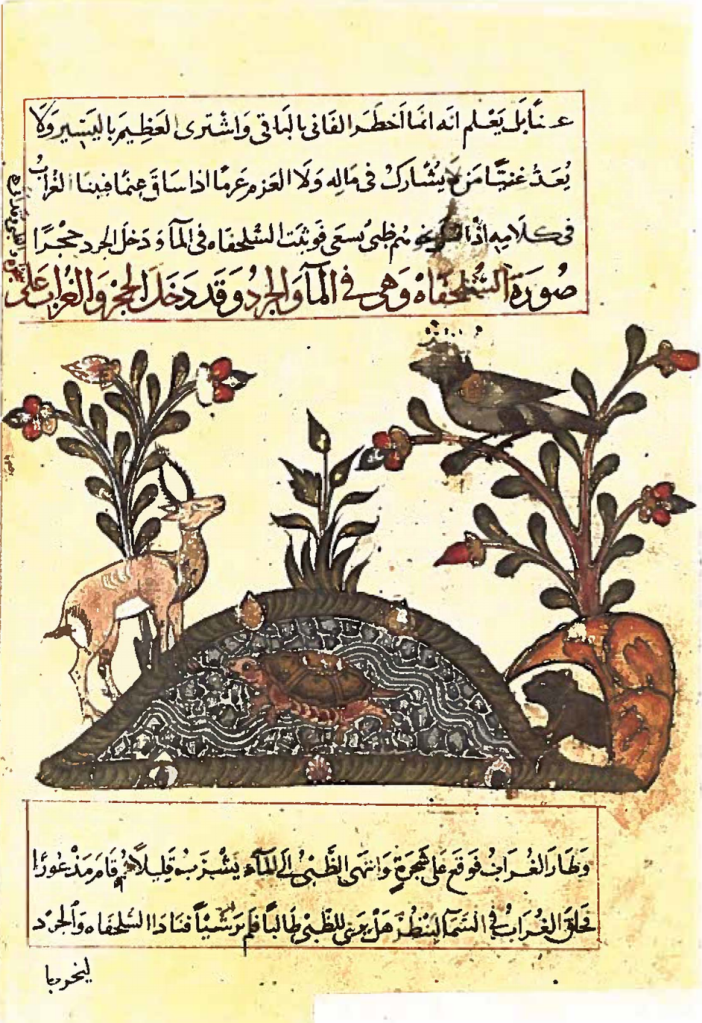

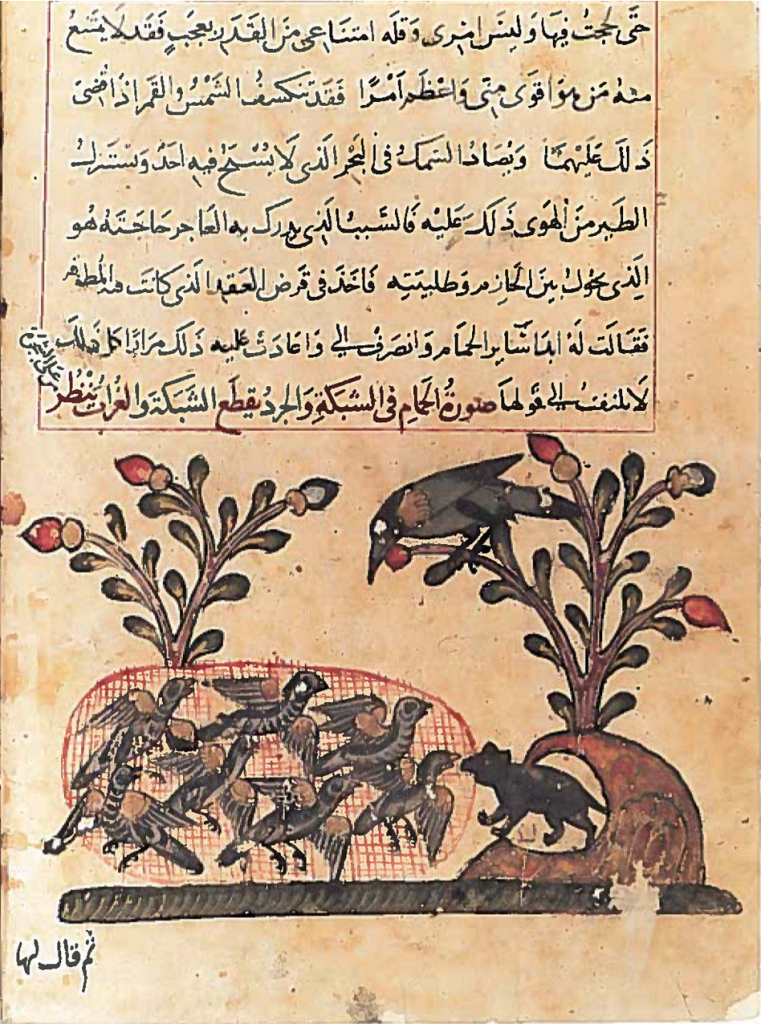

One fable I found interesting within Kalila wa Dimna is one titled “The Ringdove”. The title is somewhat of a misnomer, given that the fable’s protagonists mainly include a gazelle, a tortoise, a mouse, and a crow. Uniting together against the hunter, the group begins to develop a strong, unwavering friendship, coming together daily to “talk about their lives and experiences” and “share their meal together”. In times of danger, the animals do whatever it takes to save their companion, even if it means going against the predator. Eventually, the creatures begin to shift their relationship from a platonic one to a familial one, referring to one another as “brothers”.

In stories like Reynard the Fox and the fables by Marie de France, interspecies relationships are often portrayed very negatively. In fact, at certain points, the interactions between different animals often results in severe bodily harm or even death. For instance, in Marie’s “The Wolf and the Crane”, wanting to heal her leader, a crane successfully dislodges his throat by removing the blockage with her beak. Expecting a reward for her deed, the bird is instead met with a cruel jest, with the wolf arguing that her reward was him refraining from killing her whilst in his mouth. Rather than display gratitude, the wolf instead asserts his dominance by reminding the crane of her role as prey and his as the predator.

Meanwhile, like in “The Ringdoves”, Reynard the Fox includes an instance of interspecies bonding by having Reynard refer to Bruin the bear as his “uncle”. This relationship immediately collapses once Reynard’s trickery is revealed. Seeking to evade arrest, the sly fox gains Bruin’s trust by giving him this patrimonial title, and once the bear is ensnared in his trap, the trickster makes a quick getaway. Viciously attacked by humans and struggling to escape, Bruin severely disfigures himself and narrowly avoids death.

By referring to one another as “brothers”, the animals essentially ignore all biological relations – basing their bond on friendship rather than blood. Centering their lives around one another, this behavior eventually comes to save them numerous times, with the animals joining their skills together to save their friend in need.

The lessons are clear: Firstly, a “family” isn’t just reserved for those with blood relations; it can also be used for people whose relationships have transcended friendship and into brotherhood. Secondly, by casting aside our differences, we can unite as one, which serves especially useful when it comes to dangerous situations.

Although Kalila wa Dimna was originally meant to be a guide for kings, I believe the lessons within it should be taught to everyone – not just monarchs. Thus, if you’re looking for new reading material, I highly implore you to read a copy of this text. Even if all you manage to get out of reading it is a simple moral, you’re nonetheless taking one step closer to making the world a better place.

Works Cited

Rahimieh, Nasrin. “Mirrors for Princes.” Humanities Core Lecture. Anteater Learning Pavillion, Irvine. 26 November 2019. Lecture.